Kramer Vineyards Blog

Wine Tips, Vineyard Stories & Pairings from Gaston, OR

Featured Event: Dec 27

The Big Bubble Bash. We are opening the library to pour our entire sparkling lineup (12 wines) side-by-side.

Get Tickets ($53)Welcome to your resource for all things wine! From expert pairing tips and behind-the-scenes vineyard stories to seasonal inspiration, discover the artistry and passion behind every bottle.

Join our newsletter for the latest releases, exclusive event invites, and winemaker notes.

Join Our Mailing ListThe Difference Between Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, and Pinot Noir Blanc

The Science of the Pinot Family

Pinot Blanc, Pinot Noir Blanc, and Pinot Gris all stem from the remarkable Pinot Noir grape. While they look and taste different, it is essential to recognize that all three are genetic clones of Pinot Noir.

They are not different species; they are distinct mutations of the same vine. Despite their shared lineage, they have developed distinct personalities. Delve into their flavor profiles below to fully appreciate the nuances within the Pinot family.

Did you know?

We use these unique Pinot clones to create our signature Sparkling Wines. Join us Dec 27 for the Big Bubble Bash to taste 12 of them side-by-side (including our library Pinot Blanc bubbles!).

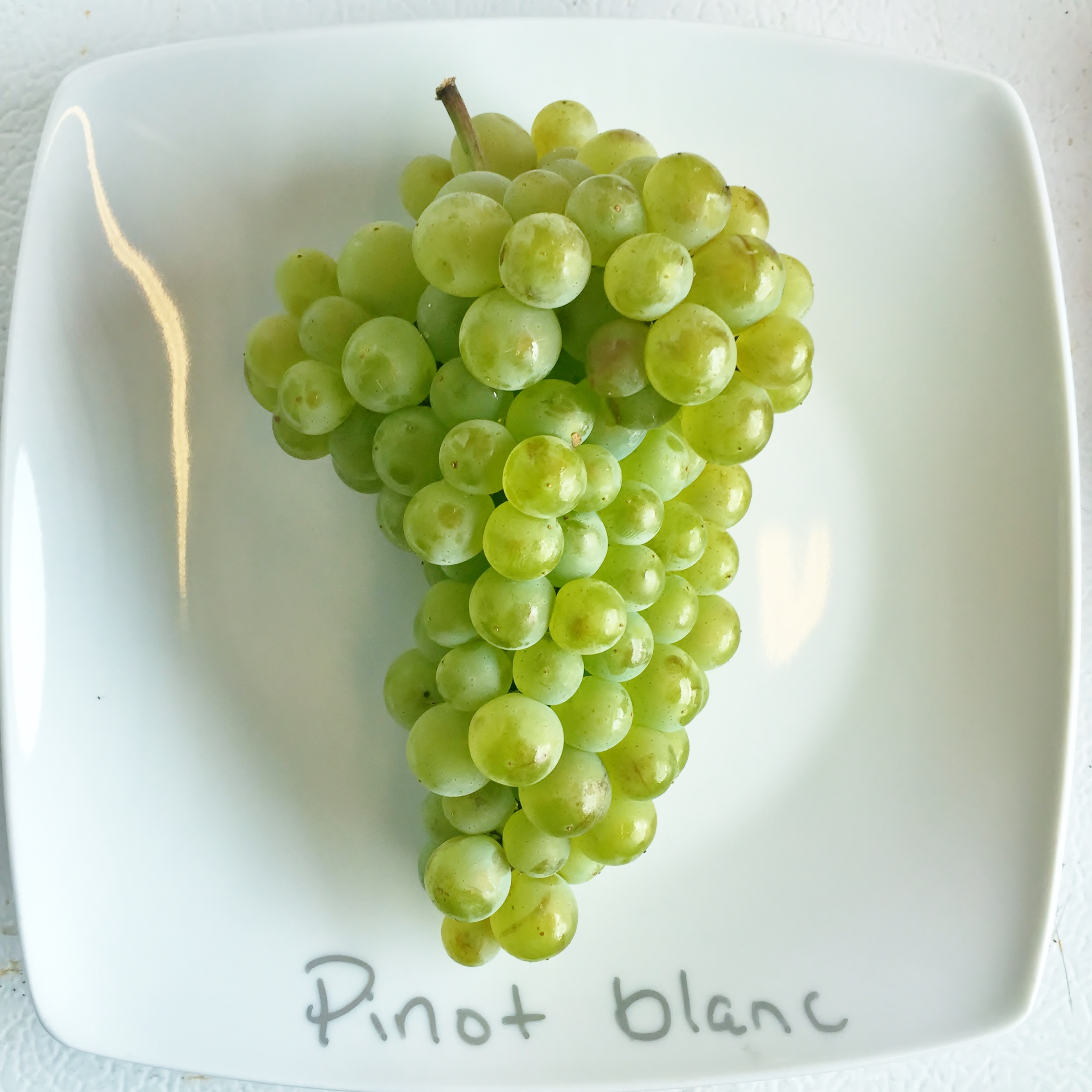

1. Pinot Blanc

Pinot Blanc is a genetic mutation of Pinot Noir that affects the pigment of the grape skin. It is renowned for its elegance and is often referred to as "the poor man's Chardonnay" in Burgundy, though we believe it deserves top billing.

The Profile: Delight your senses with bright notes of zesty lemon, succulent pear, crisp apple, and delicate apricot. You'll often discover a subtle undertone of almonds and a stony minerality.

In Our Vineyard: Despite being a cool-climate grape, Pinot Blanc is late-ripening. It thrives in our Yamhill-Carlton AVA, retaining freshness and purity.

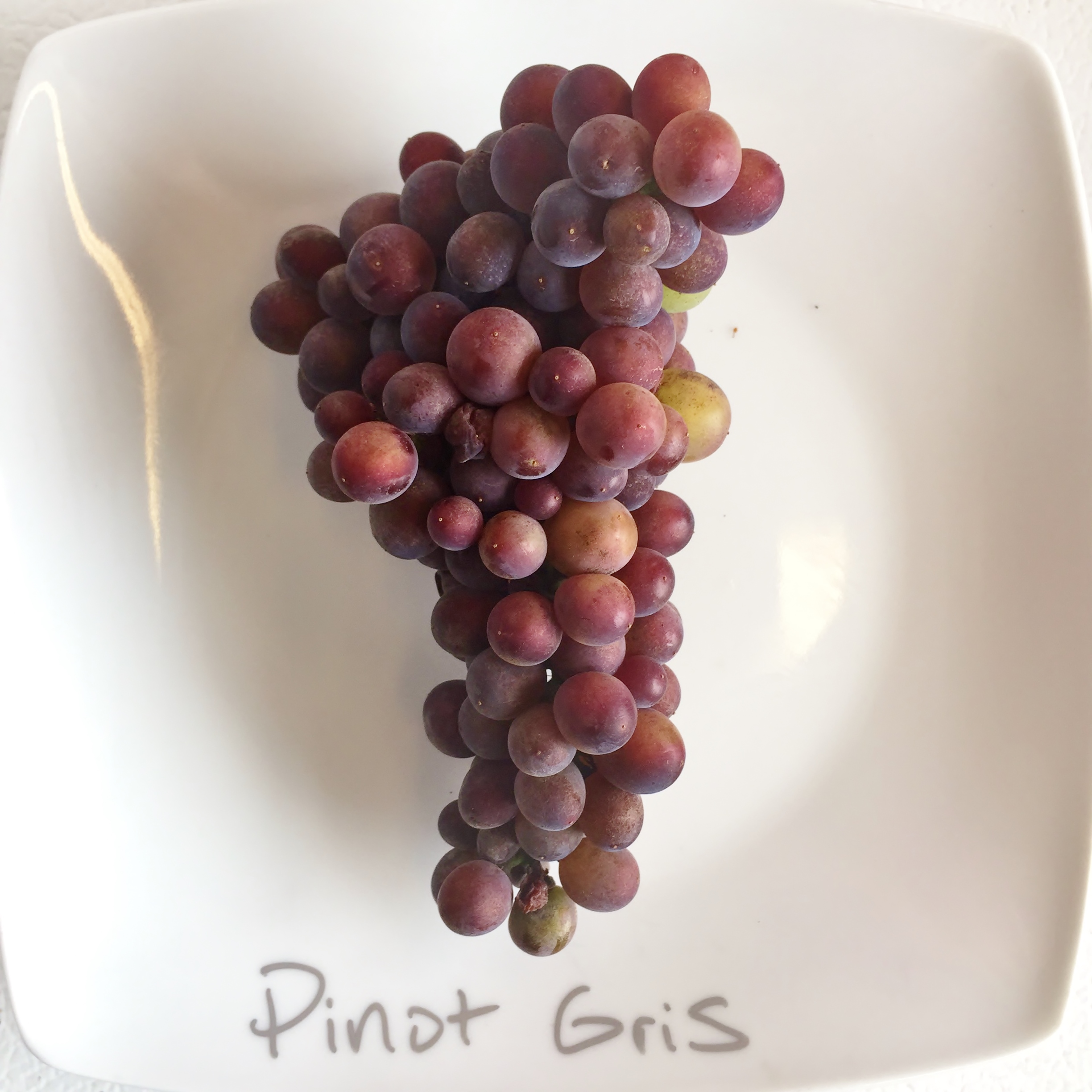

2. Pinot Gris

Pinot Gris ("Gray Pinot") is born from a mutation that leaves the skins with a stunning mauve/gray hue at harvest. While Pinot Noir is a red wine, Pinot Gris takes on a completely different persona.

The Profile: Indulge in luscious notes of ripe apple and juicy pear, interwoven with a delicate touch of honey. As you explore further, you'll encounter hints of flint and spearmint.

The Style: We prefer our Estate Pinot Gris to be dry, allowing the bracing acidity and steely minerality to shine through.

3. Pinot Noir Blanc

This is the "trickster" of the family. Pinot Noir Blanc is a white wine made from red grapes.

How it's made: The juice of almost every grape is clear. The color comes from the skins. For Pinot Noir Blanc, we handpick red Pinot Noir grapes and press them immediately, separating the juice from the skins before any red color can leach out.

The Profile: Prepare to be enchanted by aromas of crisp apple, peach, and honeydew melon. It has the weight and texture of a red wine, but the crisp flavors of a white.

Taste the Difference

At Kramer Vineyards, we are dedicated to exploring every facet of the Pinot grape. Whether you appreciate the refined elegance of Pinot Noir Blanc or the captivating flavors of Pinot Gris, we invite you to taste them side-by-side.

*Intrigued by the red wine expression? Shop our Estate Pinot Noir here.

A Kramer Family Holiday Tradition: How We Select Wines for the Feast

A Kramer Family Holiday Tradition

Every year, as our family gathers around the holiday table, choosing the wines we'll share is more than a decision—it reflects our life's work. Welcome to our family's feast tradition, where every bottle tells a story. Here's how we, the Kramers, select wines for our own celebrations.

1. Starting with Sparkle

The celebration always begins with a sparkle. Vineyard owner Keith Kramer believes in welcoming guests with Sparkling Wine. It's a gracious way to greet loved ones and set a festive tone. As guests gather in the kitchen, our go-to bubbles seamlessly transition from the welcome toast to the appetizers.

Love Sparkling Wine?

We are opening our library for a special post-holiday event. Join us Dec 27 for the Big Bubble Bash! We will be pouring our entire sparkling lineup (12 wines) side-by-side.

2. Nouveau Delights: A Fresh Tradition

Since 2018, Nouveau wines have held a special place in our holiday tradition. Their low tannin and fruity profiles make them the perfect pairings for turkey, ham, and roasted vegetables. This year, we are pouring the 2025 Nouveau Wines, offering bright fruit notes and a lively spirit that keeps the palate refreshed.

3. Bright Whites for Balance

When it's time to take our seats, every setting boasts a white wine glass alongside a red. We’ve found that lighter white wines like our Estate Pinot Gris and Müller-Thurgau are perfect for offsetting the richness of gravy and stuffing. They act as a "reset button" for your tastebuds between rich bites.

4. Rosé: The Culinary Chameleon

Rosé is a culinary all-star. With elements of white and red wines and a hint of red berry fruits, a Dry Rosé finds its place among cranberries and glazed hams. It is arguably the safest bet on the table—everyone loves it, and it pairs with everything.

5. Pinot Noir: The Main Event

For us, Pinot Noir takes center stage. Its higher acidity, lower tannins, and notes of earthiness create a perfect dance with savory holiday dishes. We especially relish sharing aged Pinot from our private collection for special occasions like Christmas dinner. If you have a bottle of Pinot Noir Heritage in your cellar, this is the week to open it.

From our family to yours, may your celebration be filled with warmth, joy, and exceptional wines.

Share this tradition:

Incorporating Kramer Sparkling Wines into Everyday Life: Beyond New Year's Eve

Incorporating Sparkling Wines into Everyday Moments

At Kramer Vineyards, sparkling wines aren't just for weddings or New Year's Eve celebrations. We'll inspire you to infuse the joy and effervescence of our sparkling wines into your everyday life. From intimate gatherings to casual brunches and moments of personal celebration, we'll provide ideas and suggestions to make every day sparkle with Kramer Vineyard's unique charm.

Embracing Sparkling Wine in Everyday Moments

Let me share a delightful story from my time as a harvest intern in Burgundy, where I discovered a charming custom that forever changed my perspective on sparkling wine. In Burgundy, the land of prestigious vineyards and rich traditions, sparkling wine holds a special place in both grand celebrations and everyday moments of togetherness. Whether it's the joyous La Paulée, the extravagant celebration marking the end of the grape harvest, or simply being a guest in someone's home, it is customary to open a bottle of champagne and serve a salty snack, embracing the effervescence and creating unforgettable memories.

Inspired by our Burgundian friends, we have embraced the essence of this tradition at Kramer Vineyards and incorporated it into our tasting room. As soon as you step through our doors, you are greeted with the effervescent joy of sparkling wine. We believe that every day holds its own reasons to celebrate, and what better way to honor those moments than with a glass of sparkling wine in hand?

Sparkling Wine: Elevating Everyday Occasions

Everyday Gatherings: Whether it's a cozy dinner with loved ones or a relaxed get-together with friends, incorporating sparkling wine adds a touch of elegance and celebration to these intimate moments. Toast to cherished connections and create lasting memories with our exquisite sparkling wines.

Brunch Delights: Elevate your brunch experience by serving our sparkling wines alongside delectable dishes. The effervescence and vibrant flavors complement a variety of brunch favorites, from eggs Benedict to freshly baked pastries. Sip, savor, and let the sparkle enhance your leisurely mornings.

Personal Milestones: Life's achievements, big or small, deserve to be celebrated. Raise a glass of Kramer Sparkling Wine to honor personal milestones, whether it's a promotion, graduation, or simply a moment of personal triumph. Let our sparkling wines be the companions that add a touch of glamour and significance to your journey.

Creating Everyday Moments of Celebration

Incorporating sparkling wine into your everyday life is about embracing the enchantment of the present moment. Here are a few ideas to infuse everyday moments with the charm of Kramer Vineyard's sparkling wines:

- Unwind and Relax: Treat yourself to a moment of relaxation with a glass of sparkling wine after a long day. Whether you're indulging in a bubble bath or enjoying a peaceful evening on the patio, let the effervescence transport you to a realm of tranquility and bliss.

- Picnic Pleasures: Plan a delightful picnic in the park or your backyard and pack a bottle of our sparkling wine. Sip it as you bask in the sun, savoring the flavors and the company of loved ones. The sparkling wine's effervescence and refreshing nature make it a perfect companion for outdoor adventures.

- Unexpected Surprises: Surprise a loved one with a special moment of celebration. Whether it's breakfast in bed, a spontaneous rooftop picnic, or a candlelit dinner, let the pop of the sparkling wine cork be the signal of joy and delight. Share laughter and create memories that will be cherished for years to come.

Pet-nat and street tacos are a winning combination!

Beyond New Year's Eve, Kramer Vineyard's sparkling wines are here to elevate your everyday life. By incorporating the joy and effervescence of our wines into intimate gatherings, casual brunches, and personal celebrations, you can infuse every day with a touch of sparkle. Experience the unique charm of Kramer Vineyard and discover how our sparkling wines can enhance your special moments. Visit our website to explore our exquisite collection and start making every day sparkle with Kramer Vineyard's sparkling wines. Cheers to a life full of joy and celebration!

Share this post:

The Art of Evaluating Pinot Noir in the Barrel

Benefits of Barrel Aging Pinot Noir at Kramer Vineyards

As passionate winemakers at Kramer Vineyards, we always focus on bringing out the most authentic expression of the fruit we grow in our estate vineyard. Barrel aging is pivotal in this pursuit, offering many benefits that enhance and complement our wines.

At Kramer Vineyards, our barrel selection and aging regime are meticulously crafted to ensure that the barrels serve as vessels for aging and act as partners in the winemaking process. After all, we don't grow and make barrels; we grow and make wine!

The use of oak barrels in aging Pinot Noir presents various advantages that contribute to the wine's ultimate expression and exceptional quality. Let's delve into some of the key benefits:

Enhanced Complexity

The interaction between Pinot Noir and carefully selected French oak barrels introduces subtle nuances and flavors that add depth and complexity to our wines at Kramer Vineyards. Each barrel, with its unique characteristics influenced by the forest, tightness of the grain, and the cooper's building and toasting techniques, contributes to the wine's distinct personality.

Improved Structure and Tannins

Oak barrels play a crucial role in enhancing the structure of our Pinot Noir. The tannins extracted from the oak integrate with the wine, providing a refined and balanced mouthfeel. This added structure not only enhances the wine's aging potential but also contributes to a more robust and layered tasting experience.

Aromatic and Flavor Contributions

The toasting process of oak barrels imparts delightful aromatic compounds and flavors to our Pinot Noir. Notes of vanilla, spice, and toasted nuts are subtly woven into the wine, complementing the fruit's natural characteristics and adding a luxurious touch to each sip.

Micro-Oxygenation

Barrel aging allows for gentle micro-oxygenation, a process where small amounts of oxygen permeate the barrel and interact with the wine. This slow and controlled exposure to oxygen helps soften the tannins, enhance the wine's texture, and promote the development of complex tertiary aromas and flavors over time.

Stability and Longevity

Oak barrels contribute to the overall stability of our Pinot Noir by promoting the polymerization of tannins and color compounds. This stability enhances the wine's ability to age gracefully, allowing it to develop and evolve beautifully in the bottle for years to come.

At Kramer Vineyards, the art of barrel aging is an integral part of our winemaking philosophy. By carefully selecting and utilizing oak barrels, we can enhance the complexity, structure, and overall quality of our Pinot Noir, creating wines that are truly exceptional. Experience the exquisite results of our barrel aging process by exploring our collection of wines.

Share this post:

Pinot Noir is a Wine that Rewards Patience

Patience is vital when evaluating a barrel of Pinot Noir. During the early months, the wine exhibits vibrant primary fruit flavors with acidity and tannins that may initially seem disjointed. However, a magical transformation occurs as the wine "winters over" and undergoes malolactic fermentation.

Malolactic: it's Fantastic

Malolactic fermentation, where beneficial bacteria convert sharp malic acid into smoother lactic acid, softens the wine's acidity and enhances its complexity, mouthfeel, and perception of tannins. This process gradually shapes the wine, unlocking a rounder and more integrated character and showcasing a stunning depth of flavors.

At Kramer Vineyards, we understand the significance of each barrel in shaping the aging Pinot Noir. The unique characteristics influenced by the terroir of Willamette Valley, the cooper's craftsmanship, and the evolution with each fill contribute to the wine's complexity and depth.

As barrels are reused, they lose their potency, imparting fewer flavors and tannins to the wine. This aging tradition adds depth and complexity to our wines, requiring us to carefully consider the number of fills for each barrel to maintain the desired balance.

When the wines have completed malolactic fermentation and settled back into the barrel for further aging, it marks a pivotal moment in their development. This is an opportune time for us as winemakers to assess their qualities and draw connections to past vintages, guiding our blending decisions to ensure the final expression of the wine aligns with our vision.

Through the meticulous evaluation of Pinot Noir during its barrel aging journey, we can determine how to serve the wine best as we head toward bottling. Each barrel holds the potential to reveal unique characteristics that showcase the terroir of Willamette Valley. Join us at Kramer Vineyards as we invite you to experience the art of evaluating wine in the barrel, appreciating its benefits and extraordinary expression of this captivating grape variety.

Barrel Tasting Pinot Noir at Kramer Vineyards

If you'd like to schedule a barrel tasting at Kramer Vineyards, please get in touch with us for more information or to book your tasting experience. Email us at kim@kramervineyards.com.

The Art of Dosage: Transforming Sparkling Wines with a Delicate Touch

Have you ever wondered what dosage means in champagne and sparkling wine? Allow us to shed some light on this vital aspect of the winemaking process.

Have you ever wondered what dosage means in champagne and sparkling wine? Allow us to shed some light on this vital aspect of the winemaking process.

Dosage refers to the addition of a finishing syrup after the second fermentation in the bottle. This step involves carefully introducing small amounts of sugar to the wine. The purpose of dosage is multi-fold: it helps to balance the naturally high acidity of the wine, accentuates its fruit flavors, contributes to a smoother texture, and so much more.

We highly recommend reading this interview with noted Champagne expert Peter Liem by wine writer Jaime Goode for a comprehensive and insightful read on dosage, grower-producers, and viticulture. It provides a holistic understanding of the role of dosage in creating exceptional sparkling wines.

In our cellar, we eagerly anticipate the moment we get to taste our sparkling wines shortly after bottling. The wine is dry, effervescent, and alive with suspended yeast cells at this stage. It never fails to be a thrilling experience.

In our cellar, we eagerly anticipate the moment we get to taste our sparkling wines shortly after bottling. The wine is dry, effervescent, and alive with suspended yeast cells at this stage. It never fails to be a thrilling experience.

Once the second fermentation is complete, we carefully evaluate the need for dosage. We prepare a range of wines with varying sugar levels, up to 10 grams per liter. Throughout our winemaking history, we have bottled sparkling wines with dosages ranging from 3 to 8 grams per liter. However, we must admit that we also have a soft spot for crisp, tart, and bone-dry wines that don't require any additional dosage.

As a sparkling winemaker, my perspective on dosage has evolved significantly. When younger and less experienced, I preferred the romance of a perfect, raw sparkling wine without dosage. I have since learned that when the dosage is employed judiciously, it can elevate a wine and bring out its true essence in a way that remains authentic to the terroir and vintage (while leaving room for zero-dosage wines when that's the best expression of these qualities).

While the movement towards lower or zero dosage has gained traction over the last two decades, particularly among grower-producers emphasizing terroir expression, I have come to appreciate the transformative potential of dosage when used thoughtfully and in harmony with the wine's character.

Today, I invite you to join me in a deeper exploration of dosage's intricate role in champagne and sparkling wine. Let us take a moment to cherish how dosage contributes to the delightful flavors, textures, and nuances that unfold in every glass. If you are intrigued to experience the range of our sparkling wines, please visit our website or contact us for more information.

Together, let's toast the exquisite art of dosage and celebrate the wondrous journey of Kramer sparkling wines. Cheers to the magic that unfolds in each bottle!

A Journey through 27 Blocks: Unveiling the Essence of a Singular Vintage

Unveiling the Tapestry of 27 Blocks:

A Symphony of Flavors:

The Story of Vintage:

A Wine for the Curious Palate:

As we conclude our journey through the exquisite 27 Blocks, we invite you to immerse yourself in the world of this singular vintage. From the artful co-fermentation to the harmonious blend of nine distinct grape varieties, every bottle tells a story meant to be savored and shared. Experience the essence of our estate vineyard in each glass, and let the flavors transport you to the sun-soaked hills and cool valleys where the grapes ripened. Discover the magic of 27 Blocks and allow its captivating charm to leave an indelible mark on your wine-loving heart.

The label is a patchwork quilt, representing the blocks of grapevines in our vineyard.

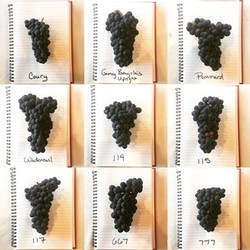

Game of Clones: Pinot Noir

I never really gave a clonal choice too much thought until recently. As a second-generation winemaker with an established vineyard, our clonal selections were made many years before I decided to pursue a career in wine. Why focus on this aspect when so many variables are at play—soil type, elevation, vine density, vine age, slope, trellis system, own-rooted or grafted? Aside from the differences in ripening time, are the clones of Pinot Noir all that distinguishable, or is it trivia?

There are more available clones of Pinot Noir than any other grape variety. When we established our vineyard in 1984, three clones were available: Pommard, Wädenswil, and Gamay Beaujolais. The Dijon clones, such as 114, 115, 667, etc., began entering Oregon in the late 80s and early 90s. These clones may differ in several ways—cluster size and shape, berry size, color, early or late ripening, etc. Now there are over 50 clones of Pinot Noir available in the United States, and we’re up to 9 at our estate.

As interest in these new clones has increased, we began to study them more closely in our vineyard. The higher crop levels in 2014 led us to introduce a series of single clone wines of Pinot Noir: Dijon 115, Dijon 777, and Pommard. We followed similar winemaking protocols for these to allow for the most explicit clonal expression possible. The fruit was harvested by hand, and 25% whole clusters were layered on the bottom of 1-ton vats and topped with destemmed fruit. After a 5-day cold soak, fermentation began. The must was pumped over, punched down twice daily, and pressed at dryness. The wine was aged in neutral French oak barrels for 14 months and bottled.

This limited collection is available in our online store.

2017 Harvest Report

Bud Break Through Veraison

With our fullest crop in years, and a warm and dry forecast, we were on track for a big harvest. 2017 had some catching up to do for heat units, and by early September our GDDs were even with 2016. This, combined with low disease pressure, and an anticipated late September/early October harvest contributed to our decision to do minimal cluster thinning. In these conditions, carrying a heavier crop load forces the vine to work harder, slowing down ripeness, resulting in more balance.

With our fullest crop in years, and a warm and dry forecast, we were on track for a big harvest. 2017 had some catching up to do for heat units, and by early September our GDDs were even with 2016. This, combined with low disease pressure, and an anticipated late September/early October harvest contributed to our decision to do minimal cluster thinning. In these conditions, carrying a heavier crop load forces the vine to work harder, slowing down ripeness, resulting in more balance.

Six Weeks of Harvesting

On the Crush Pad and in the Cellar

For the white wines, fermentations were steady and healthy. Tank space is always a concern in years where yields are high, and in some cases, we elected to ferment in stainless or neutral barrels. In addition to barrel fermented Chardonnay, we also have Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, and Pinot Noir Blanc wintering over in barrels. These vessels will be stirred bimonthly through the spring, and either blended in with their tank counterpart to enhance mouthfeel and complexity, or be bottled on their own in the fall of 2018.

As we put another harvest behind us, the 2017s are wintering over in tanks and barrels. After the New Year, we’ll begin to taste the wines individually, and start to make blending decisions and form bottling plans. The first wines of the vintage will be available in a few months, some won’t be bottled until the spring of 2019. We are looking forward to what this record-setting harvest has in store.

Vintage vs Nonvintage in Sparkling Wines

Explore the distinction between vintage and nonvintage sparkling wines. Vintage wines reflect a specific grape harvest year, while nonvintage blends combine grapes from multiple years. In the US, wines labeled with a vintage year consist of 95% grapes from that year. Nonvintage wines, including those from Champagne, showcase the expertise of blending specialists who artfully combine base wines from different years to create a consistent house style.

At Kramer Vineyards, we have a unique approach to our sparkling wines. Our two nonvintage wines are estate-grown, showcasing the expression of our vineyard site. The composition of these wines varies, with each vintage offering its own character and style.

Notably, our Brut Reserve base wines undergo fermentation and aging in neutral French oak barrels, resulting in added richness, palate weight, and structure compared to stainless steel aging. Meanwhile, our 2015 vintage Brut stands as a wine of both place and time, benefiting from that year's warm and balanced fruit. With an increased proportion of Pinot Meunier in the blend, this vintage exhibits enhanced midpalate presence and fruity aromas. The fruit for this wine is sourced from dedicated blocks within our vineyard, and the blend is carefully determined based on the yields at harvest.

The nonvintage wines in the glass present a fine, delicate mousse with pronounced yeastiness and a focus on tree fruit flavors. On the other hand, the vintage wines captivate with their fresh, light nature, featuring a delicate and abundant bead and showcasing minerality and citrus notes. As these young wines evolve in the bottle, their tone and texture will transform, making it a thrilling journey to witness their progress.

Discover the nuances between vintage and nonvintage sparkling wines, the art of blending and the expression of our vineyard site, through the exceptional offerings from Kramer Vineyards.

Shop Kramer Sparkling Wines

2014 Whole Cluster Fermentation in Pinot Noir

What is Whole Cluster Fermentation?

What is Whole Cluster Fermentation? This refers to fermenting entire bunches of grapes, stems and all. Our grapes typically go through a de-stemmer, a machine that knocks the berries off the stems. In the process, many of the berries split and release juice immediately. When we bypass that step, the fruit stays intact longer, removing the sugar available to the yeast more slowly. This results in fermentations that take longer to complete at much lower temperatures. The shift in fermentation kinetics, along with the presence of the stem, impacts the aroma, flavor, and structure of the wine. Are these features beneficial to the overall quality? How much of the whole cluster is the ideal amount, if any? Will our ideas about this change as the wine ages? With the vintage? These are all questions we hope to answer through our whole cluster series.

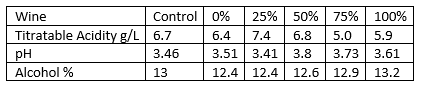

The Experiment

In 2014, we harvested five tons of Pinot Noir from the same part of the vineyard and separated the fruit into five fermenters. We added a whole cluster layer in four of these vats, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%. The fifth bin was all destemmed. We proceeded with our typical fermentation management protocols, with pump-overs and punch-downs twice daily and pressed at dryness. The wines were aged in older French oak barrels and bottled in the winter of 2016.

Owner Keith Kramer, filling vats with destemmed Pinot Noir

The Results

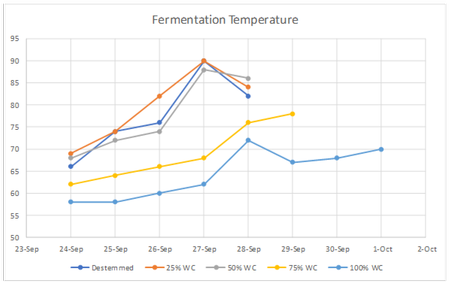

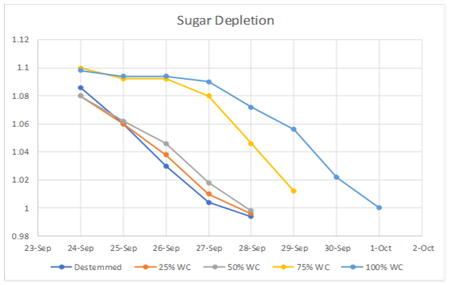

We observed differences in the fermentation kinetics almost immediately. The vats with higher percentages of the whole cluster fermented at lower temperatures:

This also correlates with the fermentation rate, as indicated by the speed of sugar depletion.

Utilizing whole cluster fermentation as a technique seems to result in slower fermentation with lower temperatures. Cool, right?

Technical Details

We found that the chemistry of the finished wines was varied, although this could be due to differences in ripeness levels in the field and clonal differences throughout the block. It is important to note that each vintage is unique, so to learn anything meaningful from this exercise, we will need to repeat the experiment over multiple vintages in varying conditions.

The Wines

Our 2014 whole cluster Pinot Noir set includes one bottle of each experimental wine and the 2014 Pinot Noir Yamhill-Carlton, for six bottles. This collection is a lovely gift and fun to share at a dinner party or with friends.

Update: The 2014s are sold out, but the experiment was replicated in 2015. You can find those wines here >>