🍇 Kramer Vineyards Blog: Discover Wine Tips, Stories, and More 🍷

Welcome to the Kramer Vineyards blog, your go-to resource for all things wine! From expert pairing tips and behind-the-scenes vineyard stories to seasonal inspiration, discover the artistry, history, and passion behind every bottle. Explore our latest articles and uncover new ways to enjoy exceptional wines.

Never Miss a Story!

Subscribe to the Kramer Vineyards newsletter for the latest wine tips, pairings, and stories.

The Other 4%: Exploring Unique Oregon Wine Varietals at Kramer Vineyards

Did you know that 96% of the vineyard acreage in the Willamette Valley is dedicated to Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, and Chardonnay? While these noble varieties have captured the spotlight, an exciting world of alternative Oregon wine varietals is waiting to be explored. At Kramer Vineyards, we invite you to venture beyond the familiar and discover "The Other 4%."

The Alternative Varietals at Kramer Vineyards

While Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, and Chardonnay may be the stars of the Willamette Valley, we have been passionate about cultivating lesser-known varietals that thrive in our unique terroir. Let's dive into the intriguing characteristics of Grüner Veltliner, Müller-Thurgau, Pinot Meunier, Carmine, and Marquette.

Müller-Thurgau: A Hidden Gem

Müller-Thurgau, a relatively unknown varietal, has found a thriving home in our vineyards since the mid-1980s. Its story at Kramer Vineyards began when owner Keith Kramer took a vineyard management class in the early 1980s. During the class, he encountered a fellow enthusiast who couldn't contain their excitement about Müller-Thurgau for Oregon. Intrigued by the fervor, Keith decided to explore this grape further.

"We bought some when we had the opportunity in the mid-80s," Keith recalls. The wine made from Müller-Thurgau grapes was a hit, prompting us to plant vines at our estate. This varietal proved exceptionally productive at our site, consistently yielding flavorful fruit even in the most challenging vintages.

Since then, we've crafted various Müller-Thurgau wines, from dry to off-dry, semi-sweet to dessert, and even sparkling. Our sparkling and still wines have garnered popularity and often rank as the top sellers in our tasting room. In 2018, Wine Enthusiast recognized us as a Notable Müller-Thurgau Producer in the US, further validating our dedication to this exceptional varietal.

Indulge in the enticing flavors of peach, starfruit, lychee, passionfruit, mango, lime, gooseberry, and sweet basil that define our Müller-Thurgau wines. Experience the charm of this hidden gem and join us in celebrating the recognition and acclaim our Müller-Thurgau wines have garnered.

Grüner Veltliner: A Crisp and Versatile White

Grown on our estate since 2010, Grüner Veltliner is a remarkable white grape variety known for its crispness and expressive flavors. This Austrian favorite captivates with notes of lemon, lime, cucumber, peach, white flowers, freshly cut grass, green apple, and pear. Its high acidity and versatility make it an excellent choice for food pairing, complementing a range of dishes.

At Kramer Vineyards, we've taken the allure of Grüner Veltliner a step further by crafting a spectacular sparkling wine. The lively effervescence and elegant flavors of our Grüner Veltliner sparkling wine delight the senses. With each sip, you'll experience the vibrancy of citrus, the complexity of orchard fruits, and the refreshing zing that only sparkling wines can deliver.

Whether you savor our still Grüner Veltliner or indulge in the sparkling variation, this exceptional varietal will captivate your palate and elevate your wine experience. Join us in celebrating the versatility and sparkling brilliance of Grüner Veltliner at Kramer Vineyards.

Pinot Meunier: A Sparkling Delight

Pinot Meunier is an exceptional grape variety in our vineyards, exclusively planted, grown, and harvested for our traditional sparkling wine program. This distinctive grape adds depth and character to our sparkling wines, contributing to their unique and effervescent charm. Indulge in the enchanting flavors of cherries, blackcurrants, blackberries, tobacco, leather, and subtle spice that define our Pinot Meunier sparkling wines. With every sip, experience the artistry and dedication that goes into crafting these sparkling delights at Kramer Vineyards.

Carmine: A Heritage from California

Carmine has a fascinating history that traces back to its creation in 1946 at UC Davis by Dr. Harold Olmo. This unique grape variety is a cross of Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignan, and Merlot, developed specifically to thrive in California's cooler, coastal regions. Although Olmo's vision for Carmine did not gain widespread popularity as intended, the vines found their way north to Oregon in the 1970s, landing at Courting Hill Vineyard in Banks. It was there that Keith Kramer, inspired by the Oregon wine legend Jim Leyden, was introduced to this intriguing grape variety. In 1989, Leyden generously gifted Kramer Vineyards with our first Carmine vines.

At Kramer Vineyards, we have dedicated ourselves to unlocking the potential of Carmine. This late-ripening, thick-skinned grape has revealed its true character through our continuous exploration in the vineyard and the winery. Our Carmine wines, known for their dark red color, exude herbaceous aromas and peppery notes. With influences from its Cabernet Sauvignon grandparent, you can expect dark fruit flavors, dark chocolate, and an occasional hint of mint. Indulge in the distinctive flavor profile of our Carmine wines, featuring dried cranberries, maraschino cherries, cinnamon, anise, bell pepper, and cracked peppercorns.

Marquette: A Challenging Yet Essential Grape

Marquette, a captivating grape variety, was planted in our vineyard in 2010 across 0.5 acres. Developed by the University of Minnesota for extremely cold climates, Marquette is not well suited to our region or our property. Its intended growing conditions are much cooler than what we have in the Willamette Valley, resulting in unique challenges for its cultivation.

One of the major obstacles we face with Marquette is its early ripening nature. The vines tend to bloom weeks ahead of other varietals, often coinciding with rain, interfering with fruit set. This presents a constant battle to ensure proper fruit development during critical growth periods.

Another challenge arises at harvest time. Due to its early ripening, Marquette is susceptible to bird predation. The birds sometimes devour the fruit before we can pick it. Additionally, the chemistry of Marquette at ripeness is unusual, often exhibiting high sugar levels and acidity, requiring careful monitoring and timing for optimal harvest.

While we wouldn't recommend planting Marquette in the Willamette Valley, we have found a wonderful use for this challenging grape. By cofermenting it with grapes sourced from throughout our estate vineyard, we create the delightful summery red wine called 27 Blocks. This cofermentation allows Marquette to shine as a base, contributing its unique character to the blend.

With its flavor profile encompassing cherries, blackcurrants, blackberries, tobacco, and leather, 27 Blocks is a captivating expression of the harmonious interplay between our vineyard's nine grape varieties. Despite the challenges of growing Marquette in our region, its contribution to creating 27 Blocks makes it an essential part of our winemaking journey.

As you explore the wonders of Oregon wine, don't limit yourself to the familiar. At Kramer Vineyards, we invite you to journey into "The Other 4%" and discover the exceptional varietals that make our region unique. From the crispness of Grüner Veltliner to the hidden gem of Müller-Thurgau, the unique expressions of Pinot Meunier, and the innovative spirit of Carmine and Marquette, each varietal tells a story that deserves to be savored. Join us in exploring flavors and expanding your wine horizons with Kramer Vineyards.

Discover the Charm of Local Wineries: Finding the Perfect Winery Near You

Are you a wine enthusiast eager to support local wineries? Whether you're a seasoned connoisseur or new to the world of wine, embarking on an adventure to explore the best wineries in your neighborhood is a delightful journey. Local wineries are cropping up in unexpected places, offering unique wines that showcase the distinct flavors of your region. Not only does supporting these wineries boost the local economy, but it also allows you to savor and appreciate the diverse flavors that your community has to offer. Let's raise a glass and discover the best wineries near you!

The Benefits of Supporting Local Wineries

Supporting local wineries extends beyond enjoying a glass of wine. By visiting and purchasing from these wineries, you contribute to the growth of the local economy and help small businesses thrive. Many local wineries prioritize sustainability in their winemaking practices, making your support good for your taste buds and the environment.

Moreover, buying wine directly from the winery is the most sustainable choice as a consumer. You reduce the carbon footprint of distribution by eliminating the need to transport the wine to a shop or restaurant.

Additionally, supporting local wineries allows you to experience your region's unique flavors and characteristics. These wineries often use grapes specific to your area, producing truly distinctive wines. By tasting and learning about these wines, you can develop a deeper appreciation for the flavors and culture of your community.

When choosing a local winery to visit, consider factors such as the types of wines you enjoy. Research wineries that specialize in the wines you're interested in tasting. Additionally, consider the ambiance you prefer, whether casual or upscale, and explore wineries that align with your preferences. Location is also crucial, so research the wineries' proximity and surrounding amenities to plan your visit effectively.

Doing Your Homework: Tasting Room Details

Before visiting a winery's tasting room, it's helpful to research ahead of time. Here are key details to consider:

- Business Hours: Check the tasting room's operating hours to align with your visit plans.

- Reservations: Some wineries require reservations, especially during peak times. Check if a reservation is needed and make one if necessary to secure your spot.

- Tasting Fees: Find out if the winery charges a tasting fee and if it's refundable with a purchase. This information helps you plan your budget accordingly.

- Wine Varieties: Get a glimpse of the winery's wine offerings. Discover their signature wines and special releases worth exploring during your visit.

- Wine Prices: While specific prices may not be listed, learn if the winery offers wines at different prices. From affordable options to higher-end selections, there's something for every palate and budget.

- Larger Parties: If you plan to visit with a larger group, contact the winery to make arrangements and ensure a smooth and enjoyable experience.

- Food Options: Inquire if the tasting room serves food or allows visitors to bring their own. Some wineries offer food pairings or partner with local eateries, enhancing your tasting experience.

- Accessibility: We believe everyone should have access to exceptional wines. Check if the winery provides accessibility features like wheelchair ramps and accessible restrooms, ensuring a comfortable visit.

- Visitor Policy: Check if the tasting room is exclusively for guests of legal drinking age or if they allow kids and dogs. This information will help you plan accordingly and avoid surprises during your visit.

- Local Accommodations: Extend your winery experience by staying nearby. Explore suggested accommodations, such as hotels, bed and breakfasts, or vacation rentals, to make the most of your visit.

Sustainability in Winemaking

As people become more environmentally conscious, sustainability in winemaking has gained significance. Many local wineries are actively reducing their environmental footprint and implementing sustainable practices.

Some wineries have embraced sustainable, organic, or biodynamic farming methods, while others utilize renewable energy sources like solar panels to power their production facilities. By supporting these wineries, you enjoy delicious wines and contribute to a more sustainable future.

Conclusion and Call to Action to Support Local Wineries

Exploring the best wineries in your neighborhood is a fun and exciting way to support local businesses while discovering new flavors and experiences. By visiting local wineries, you enjoy delicious wine, support the local economy, preserve tradition, promote sustainability, and reduce carbon emissions.

The Pinot Family: Discovering the Unique Flavors of Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, and Pinot Noir Blanc

The Difference Between Pinot Blanc and Pinot Noir Blanc

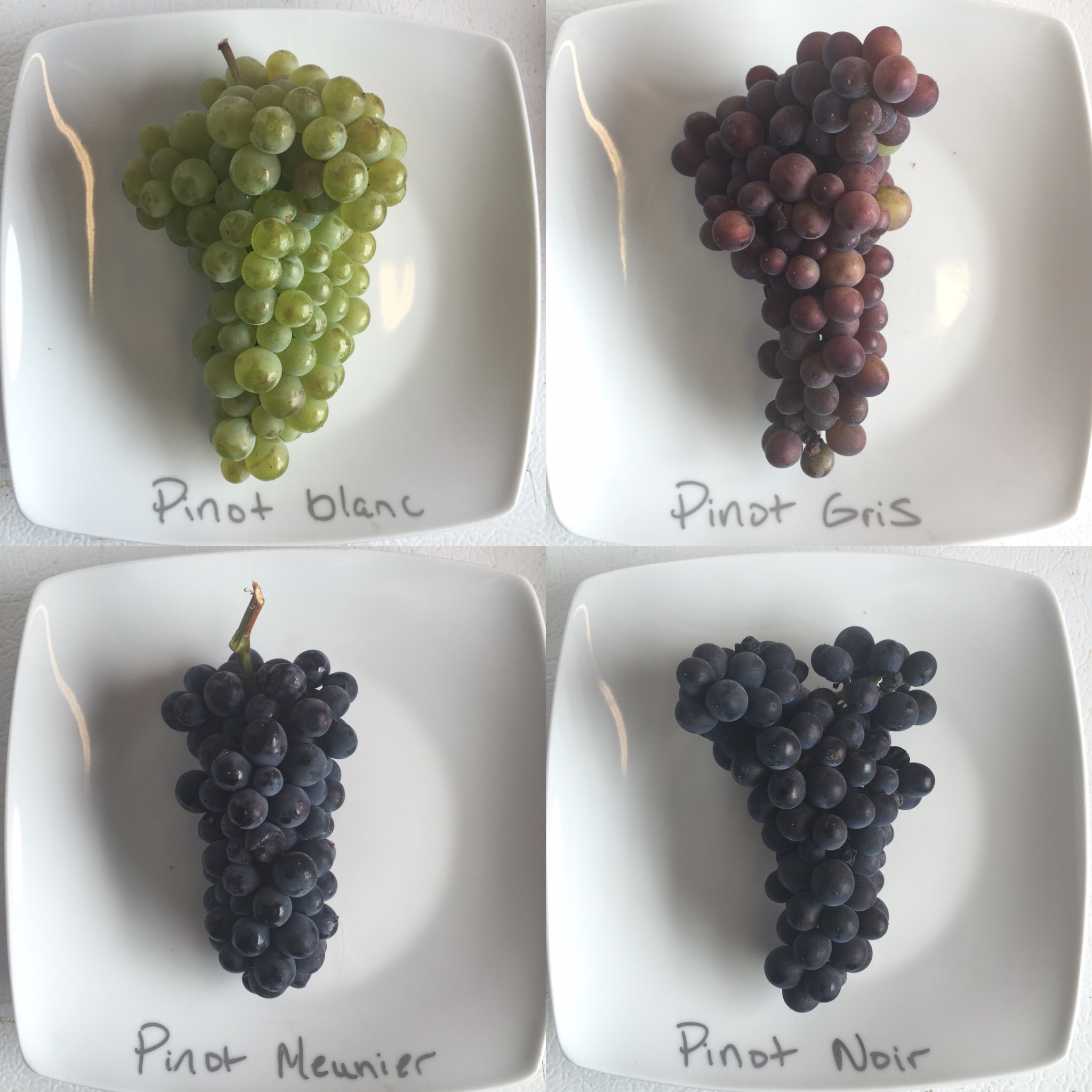

Pinot Blanc, Pinot Noir Blanc, and Pinot Gris stem from the remarkable Pinot Noir grape through clonal variations. While Pinot Blanc is crafted from white grapes and Pinot Noir Blanc from red grapes, it is essential to recognize that all three varieties are genetic clones of Pinot Noir. Despite their shared lineage, Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris have developed distinct characteristics, dispelling the misconception that they are merely different-colored versions of the same grape. Delve into their flavor profiles and features to fully appreciate the nuances within the Pinot family.

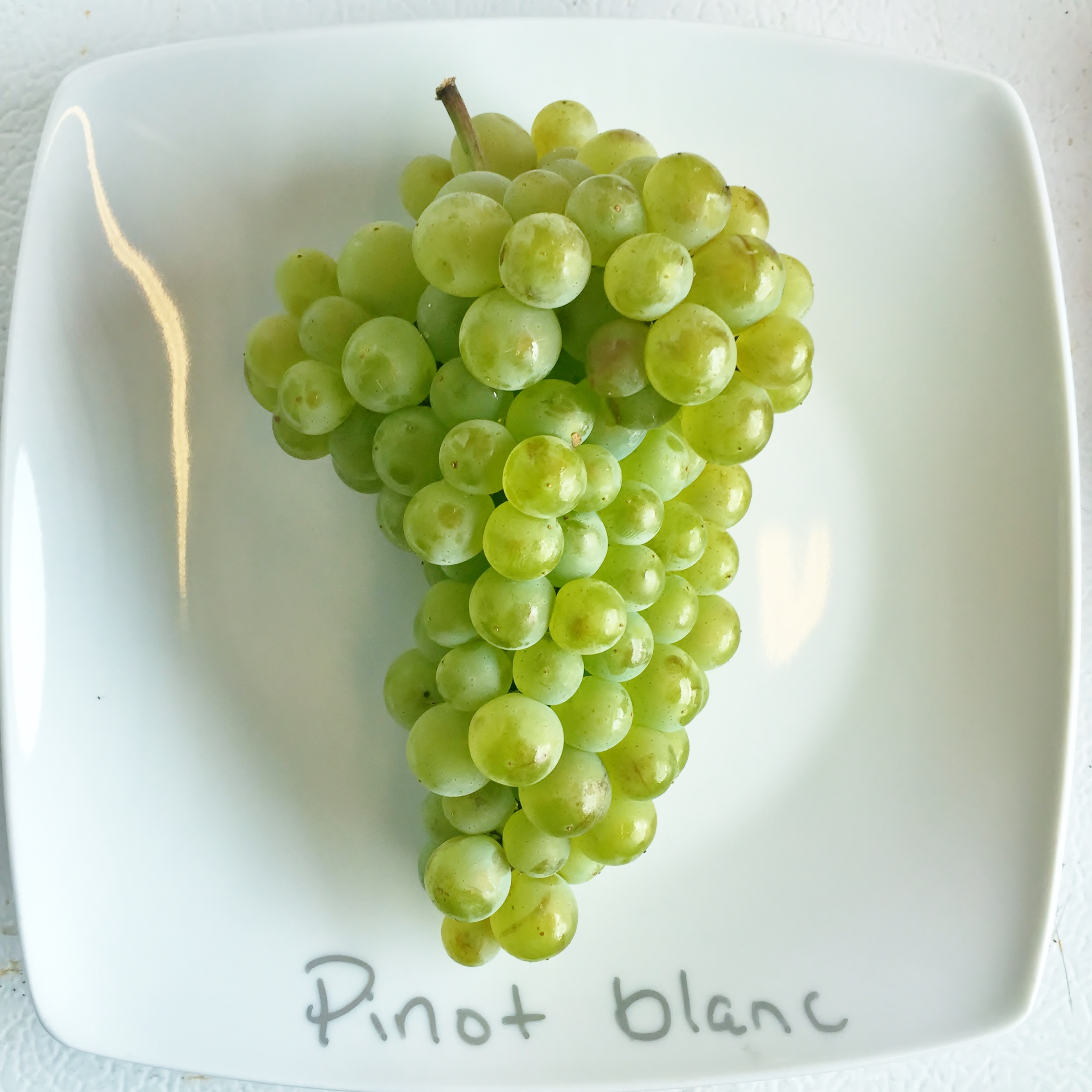

Pinot Blanc

Pinot Blanc, a distinguished clone of Pinot Noir, emerges from a genetic mutation that resulted in a captivating divergence. This mutation changes the color of the grape skins and alters the chemistry, flavor profile, and ripening characteristics. Renowned for its elegance, Pinot Blanc showcases a remarkable character both in the vineyard and the glass.

Despite being a cool climate grape, Pinot Blanc exhibits a late-ripening nature, making it one of the last grapes harvested in the Willamette Valley. Thriving in cool climates, these grapes embody the essence of freshness and purity, resulting in wines of exceptional quality.

Delight your senses with Pinot Blanc's enchanting flavor profile. Immerse yourself in the bright and refreshing notes of zesty lemon, succulent pear, crisp apple, and delicate apricot. As you savor this exquisite wine, you'll discover a subtle undertone of almonds, complemented by a compelling stony minerality that adds depth and complexity to each sip.

Explore the captivating nuances of Pinot Blanc and discover why it stands out as a distinguished white wine. From its unique genetic mutation to its late-ripening nature, this wine embodies the artistry and craftsmanship behind this exceptional grape variety. Indulge in its flavors and allow its graceful character to leave a lasting impression.

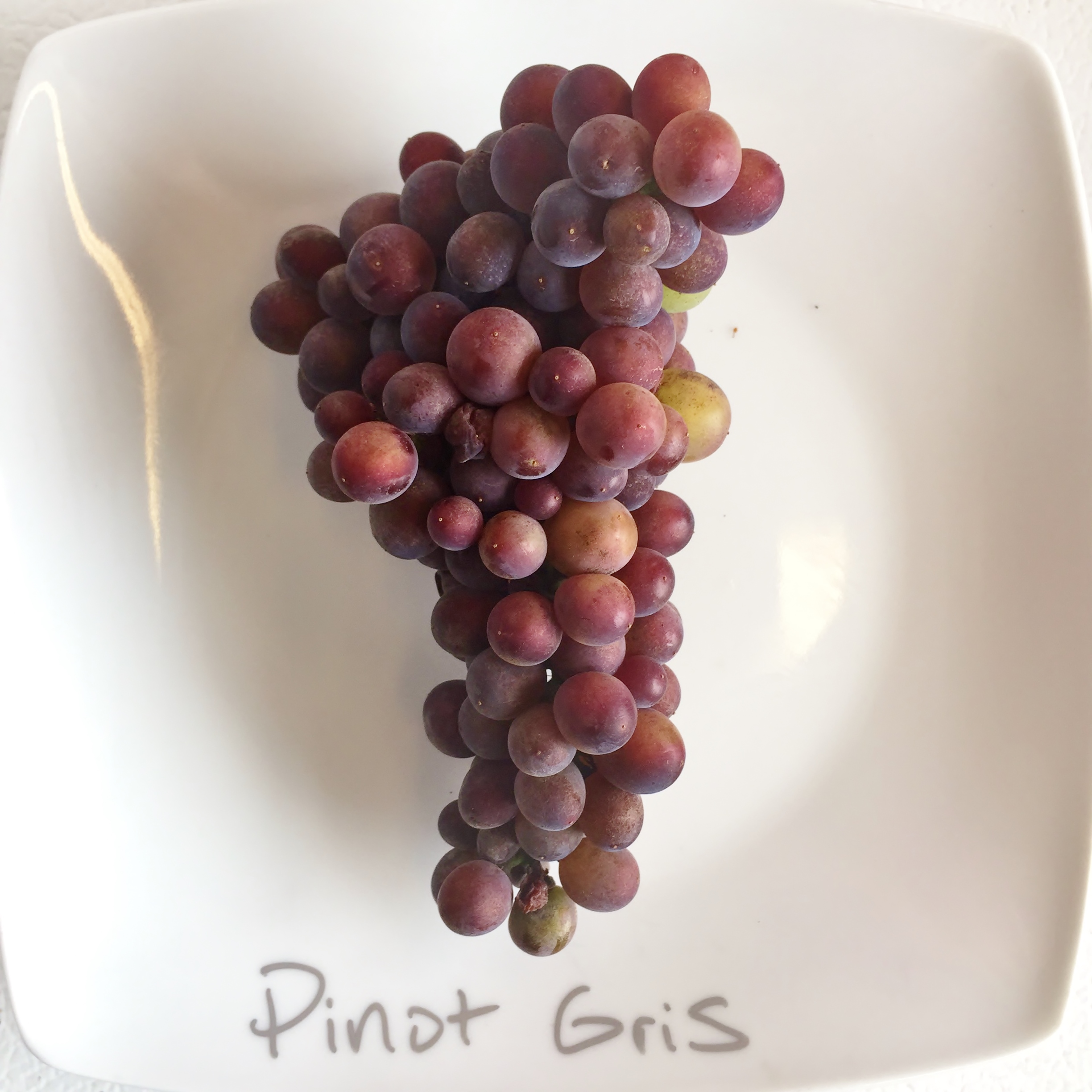

Pinot Gris

Pinot Gris, another distinguished clone derived from the illustrious Pinot Noir, offers a captivating expression of white wine that intrigues and delights. Born from a partial DNA color sequence mutation, this unique varietal manifests with stunning mauve hues in the skins at harvest, adding an alluring visual charm to the wine.

While Pinot Noir is known for its red wine characteristics, Pinot Gris takes on a different persona as a white wine. It showcases its distinct personality, setting it apart from its red counterpart.

Our cool climate single-vineyard Pinot Gris reflects the terroir and vintage, just like any other wine we produce. With its tight, dense clusters and earlier ripening than Pinot Noir and Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris thrives in our vineyard. The wines it produces are bright, with bracing acidity and steely minerality. We prefer our Pinot Gris to be dry, and the fruit from our old vines imparts impressive varietal character.

As Pinot Gris unveils its captivating flavor profile, prepare to embark on a sensory journey. Indulge in the luscious notes of ripe apple and juicy pear, interwoven with a delicate touch of honey that caresses the palate. As you explore further, you'll encounter hints of flint and spearmint, enhancing the complexity and depth of this remarkable wine. Citrus accents and the subtle essence of peach contribute to its vibrant and refreshing character, ensuring a truly memorable tasting experience.

Delve into the world of Pinot Gris and discover a wine that effortlessly balances richness and freshness, embodying the artistry and craftsmanship behind this exceptional grape variety. Compare Pinot Gris with its red counterpart, Pinot Noir, to uncover the unique characteristics that make each one stand out. Whether you're a Pinot Gris fan or exploring the differences between Pinot Gris and Pinot Noir, this journey promises to enlighten your taste buds and expand your wine appreciation.

Pinot Noir Blanc

Pinot Noir Blanc, an exquisite white wine derived from dark-skinned Pinot Noir grapes, unveils a mesmerizing expression that defies expectations. With its pristine clarity and radiant pale hues, Pinot Noir Blanc is a testament to the remarkable artistry of winemaking.

Crafted with precision, the clusters of Pinot Noir grapes are delicately handpicked and swiftly pressed immediately after harvest, limiting the extraction of color from the skins. This delicate handling ensures that the resulting wine exudes a captivating pale appearance reminiscent of liquid sunlight in a glass.

Prepare to be enchanted as you delve into the world of Pinot Noir Blanc. Immerse your senses in its alluring aroma, where crisp apple notes interplay with the subtle essence of peach. Discover the delicate nuances of clover and honeydew melon that dance on the palate, accompanied by a whisper of jasmine that adds a touch of elegance to each sip.

Pinot Noir Blanc embodies the essence of white wine sophistication, striking a harmonious balance between its vibrant fruit flavors and refreshing acidity. Its exquisite flavor profile and supple texture make it an ideal companion for culinary delights or a delightful indulgence.

Experience Pinot Noir Blanc's sheer elegance and ethereal charm, where the boundaries of white wine expression are redefined. Allow this exceptional wine to transport you to a realm of pure bliss and embrace the allure of its white wine allure.

In conclusion, the Pinot family presents a captivating array of flavors and endless exploration. Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, and Pinot Noir Blanc beautifully exemplify the versatility and depth inherent in this esteemed grape lineage. We invite you to embark on a tasting adventure, immersing yourself in these exceptional wines' intricate nuances and remarkable characteristics.

At Kramer, we are dedicated to curating a diverse selection of white wines tailored to Pinot Noir enthusiasts and those seeking Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris delights. Our collection proudly features the exquisite Pinot Noir Blanc and the captivating Pinot Gris, showcasing the remarkable versatility of this unique grape family. Whether you appreciate Pinot Noir Blanc's refined elegance or Pinot Gris's enchanting flavors, we are committed to delivering exceptional quality and creating an unforgettable wine experience for red and white wine enthusiasts.

Book a Tasting | Shop Our White Wines

*Please note: If you are intrigued by the red wine expression of Pinot Noir, stay tuned for our upcoming discussions, where we will delve into the captivating world of Pinot Noir red wines.

Five Fizzy Facts About our Celebrate Bubbly

Are you a fan of sparkling wines? If so, you're in luck because Kramer Vineyards produces some of the best Oregon sparkling wines! Here are five fizzy facts that make our wines stand out:

The Kramer estate vineyard.

100% varietal wines

Our Celebrate sparkling wines are unique varietal wines, including Pinot Noir, Grüner Veltliner, Pinot Gris, and Müller-Thurgau. We believe that each grape's flavor is best showcased on its own. The effervescence of our Celebrate wines only enhances the natural flavors and aromas of these varietals, resulting in a refreshing and perfect sparkling wine for any occasion.

Handcrafted in small batches

Due to the size of our vineyard and winery, we've always taken a small-batch approach to winemaking. With only 22 acres of estate vines and 27 individual blocks, we carefully track and evaluate each block to ensure the fruit is of the highest quality for wines of this style. This approach means we're always working with tiny lots, allowing us to pay close attention to each batch and ensure that our wines are of the highest quality.

Fresh and lively

Our Celebrate sparkling wines are not aged for extended periods like traditional method sparkling wines. Instead, we use a modern proprietary method to release the wines only a few months after harvest. This preserves the fresh, lively character of the grapes and results in a wine bursting with flavor.

Tiny bubbles

Most force-carbonated sparkling wines are injected with carbon dioxide on the bottling line, producing coarse, soda-pop-like bubbles. We believed a smaller bubble was possible with force carbonation. In 2004, owner Keith Kramer developed the system we use today. A week before bottling, the wine is transferred into a custom-built tank for pressurization. We chill the wine while gradually raising the pressure, resulting in tiny, plentiful bubbles. Our Celebrate sparkling wines are unique, high quality, and available at a lower price point than traditional sparkling wines due to the abbreviated aging process.

Sustainable winemaking

We prioritize sustainable winemaking practices to minimize our environmental impact at Kramer Vineyards. Our vineyard is dry-farmed, meaning we rely solely on natural rainfall to irrigate our vines, reducing water usage. Additionally, we use a lighter glass bottle for our Celebrate sparkling wines, which has a lower carbon footprint than traditionally made sparkling wines. From using solar panels to power our winery to implementing water conservation techniques, we're committed to preserving the beautiful Oregon wine country for generations.

Kramer Vineyards produces some of the finest Oregon sparkling wines, and we're proud to share them with you. From our 100% varietal wines to our small-batch, handcrafted approach to winemaking, we strive to create wines of exceptional quality and character. We invite you to visit our tasting room and experience our sparkling wines for yourself. Our knowledgeable staff will guide you through a tasting and share our passion for sustainable winemaking. Take advantage of this opportunity to discover some of the best sparkling wines in Oregon. Come and see us today!

Celebrate Rosé of Pinot Noir

A Beginner's Guide to Pinot Noir Clones: Q&A with Kramer Vineyards

These vines have the same DNA

What is a clone?

Pinot Noir clones are genetically identical vines propagated asexually from a "mother vine." In other words, they are vine cuttings taken from a single, original vine and grown to produce new vines. These new vines are identical to the mother vine and to one another, which allows winemakers to plant vineyards with consistent grape quality and characteristics. Pinot Noir clones can vary in their susceptibility to disease, tolerance of climatic conditions, and flavor profiles. Understanding the different features of each clone is crucial for me, as I am always looking to produce wines of the highest quality that reflect the unique terroir of our vineyard.

How do new clones of Pinot Noir arise?

Pinot Noir clones can arise through spontaneous mutations in the grapevine's DNA. These mutations create genetic variations that can change the vine's physical characteristics, such as the size or shape of its leaves or clusters of grapes. Winemakers often select and propagate clones that exhibit desirable traits, such as resistance to disease, tolerance of climatic conditions, or unique flavor profiles.

Pinot Noir has been cultivated for thousands of years, which has allowed numerous mutations to occur and be identified. While most clones originate from France, unique clones have also been identified in Switzerland, California, Oregon, and other regions. The mapping of the Pinot Noir genome in 2007 has further expanded our understanding of the genetic makeup of this grape variety and the potential for discovering new clones in the future.

Pinot Noir clones are continually evolving, and new clones may arise from spontaneous mutations. There is a possibility that the Kramer Vineyards may have a unique clone of Pinot Noir that has yet to be identified. This potential for discovery is part of what makes working with Pinot Noir clones so exciting for us.

Jumping genes are present in almost all living cells. 50% of the human genome are jumping genes; up to 90% of the maize genome are jumping genes!

Is it difficult to detect differences between clones of Pinot Noir in wine tasting?

You don't have to be a wine expert to appreciate the impact of clones on the flavor and aroma of Pinot Noir. Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc are also clones of Pinot Noir, created through mutations that affect the skin color of the grape. These mutations are so distinctive that they're often considered distinct grape varieties. We'll dive deeper into these varietals in another post. But for now, consider this: if you can tell the difference between white and red wine, your palate is expert enough to explore the nuances of Pinot Noir clones. By understanding the various clones, you can better appreciate the unique qualities of different Pinot Noir wines. For more on this topic, see Pinot Blanc and Pinot Noir Blanc: What's the Difference?

Why is it useful to know about Pinot Noir clones?

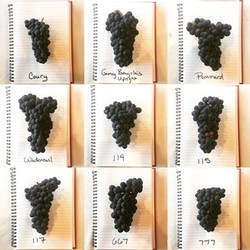

The answer for winegrowers and winemakers is simple: it allows us to choose the best clones for our specific growing conditions and wine style. For wine drinkers, knowing about clones can enhance your appreciation and understanding of the wine you're enjoying. At Kramer Vineyards, we grow nine clones of Pinot Noir and make single-clone wines from several different clones of Pinot Noir. Let's take a closer look at the characteristics of the main clones in our vineyard.

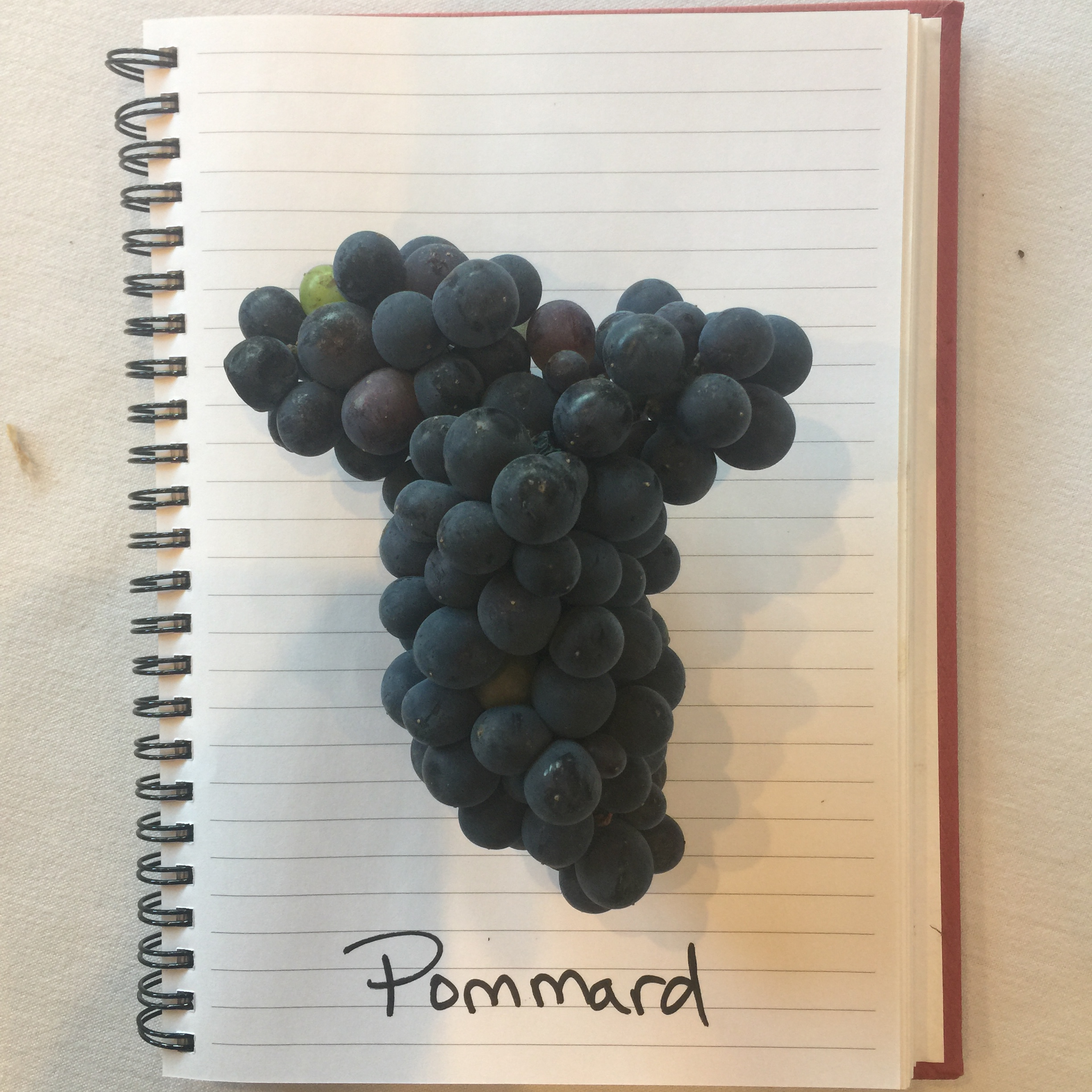

Pommard

The Pommard clone, originating from Pommard, a village in the Burgundy region of France, has made a new home in the Yamhill-Carlton AVA, where our Kramer Estate vineyard is located. It has been an essential part of Willamette Valley Pinot Noir's history and reputation, as it was one of the first clones available in the US. It is planted in many of the region's oldest vineyards, including at Kramer Estate. This clone produces medium-sized clusters, often with shoulders, and is well-suited to the cool, moist climate of the Willamette Valley.

At Kramer Vineyards, the Pommard clone was the first clone of Pinot Noir planted in 1984 and remains a significant component in many of our Pinot Noir wines, including our Estate, Cardiac Hill, Rebecca's Reserve, and Heritage Pinot Noir wines. The grapes of the Pommard clone produce balanced and elegant wines suitable for aging, which is why it is still an essential part of our vineyard. When people think of what Oregon Pinot Noir tastes like, the Pommard clone is often a big part of that reputation.

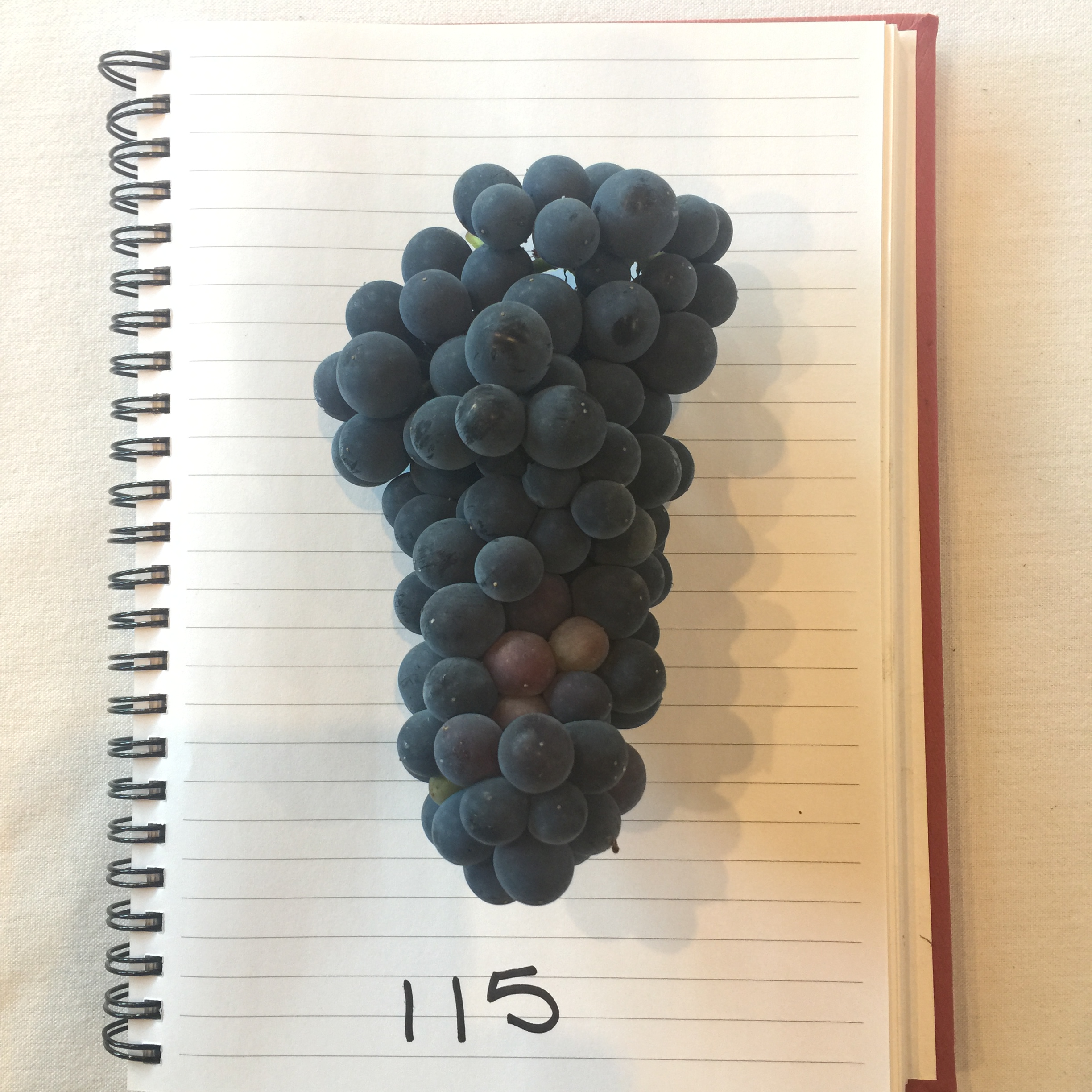

Dijon 115: The Finesse and Balance of Pinot Noir

Discover the allure of Dijon 115, a prized Pinot Noir clone hailing from Burgundy's University in Dijon. Recognized as part of the esteemed Dijon clones, Dijon 115 offers a captivating combination of early ripening, small berries bursting with intense flavors. Renowned for its finesse and balance, wines crafted from Dijon 115 grapes leave a lasting impression. At Kramer Vineyards, we were among the early adopters of this clone, planting it alongside Pommard in our esteemed Rebecca's Reserve block back in 1992. Today, Dijon 115 remains an integral component in our esteemed Cardiac Hill and Estate Pinot Noirs, showcasing its remarkable attributes year after year. Unlike other clones known for specific characteristics like spiciness or tannin, Dijon 115 stands apart as a complete wine, offering unparalleled balance and elegance. Our decision to embrace this clone was influenced by a renowned winemaker from Burgundy who attested to its surging popularity. Experience the magic of Dijon 115 and savor the harmonious symphony it brings to each glass.

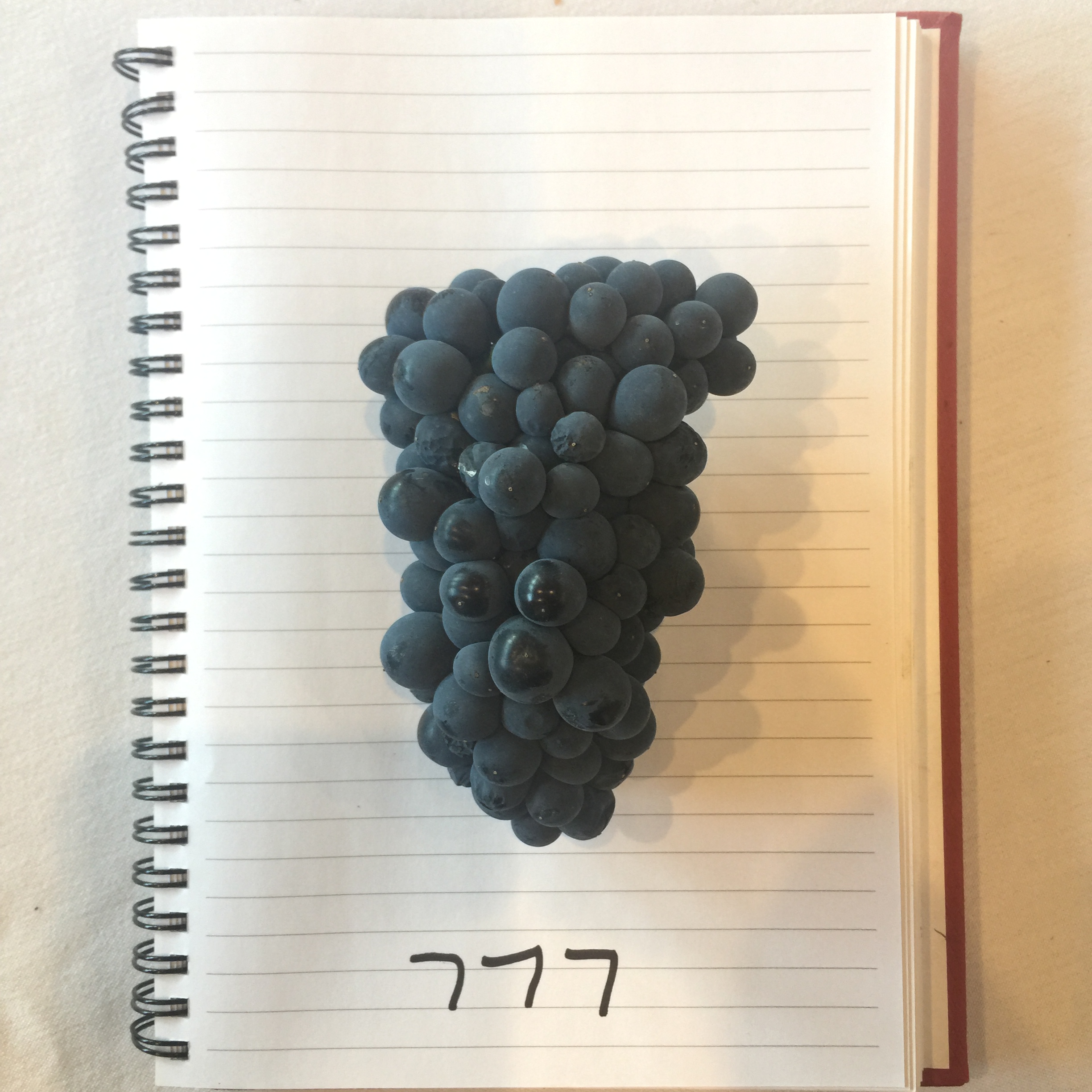

Dijon 777: Embracing Richness and Spiciness

Originating from the prestigious University in Dijon, Burgundy, Dijon 777 is an early ripening clone that gives rise to small clusters and berries, culminating in wines of intense color and pronounced tannins. Notably characterized by a captivating spiciness, Dijon 777 has become a sought-after choice for blending. Our journey with this numbered clone began in 2001 when we first planted it at Kramer Estate, integrating it harmoniously into our distinguished Estate Pinot Noir. Owner and winegrower Keith Kramer holds a special affinity for the fiery allure of Dijon 777. In 2019, inspired by a neighboring block consistently producing exceptional fruit quality, he made the bold decision to graft 0.6 acres of Muller-Thurgau to Dijon 777, tripling its acreage. The result? A tribute to the clone's undeniable character and the promise of extraordinary wines to come. Join us on this spicy exploration and experience the distinct charm of Dijon 777 in every sip.

In conclusion, while clonal selection is essential in producing exceptional Pinot Noir, it is just one piece of the puzzle. The terroir and microclimate of a vineyard site can significantly impact how a particular clone expresses itself in the resulting wine. At Kramer Vineyards, we have seen this firsthand in our 22-acre vineyard. If you're interested in exploring the unique characteristics of each clone, we invite you to visit the single clone Pinot Noir section of our online store. Here you can experience each clone's distinct personality and flavors and gain a deeper appreciation for the complex interplay of factors that create truly exceptional wines.

Meet Piquette: Wine Just Got Cooler

Discover the Delights of Piquette: A Refreshing, Sustainable Alternative

Piquette is a unique and refreshing drink that offers a delightful alternative to traditional wines. Crafted from pressed grape skins, Piquette is a lower-alcohol, lightly sparkling beverage with a vibrant flavor profile. At Kramer Vineyards, we have embraced this age-old winemaking technique to create a fizzy and refreshing drink that showcases our commitment to sustainability and innovation.

Crafting Piquette: The Art of Repurposing Grape Skins

To create our Piquette, we repurpose the grape skins that remain after the juice extraction process. These grape skins are rehydrated, allowing the release of sugars and flavors. After steeping for four days, the mixture undergoes gentle pressing, resulting in a beautiful rosy hue. The must is then fermented in stainless steel tanks, creating the delightful effervescence that characterizes Piquette.

"I saw a creative challenge in capturing so many trends with Piquette. It is the intersection of rosé, sparkling, low sugar, lower alcohol, single-serving packaging—and it's adjacent to the cider, craft beer, and hard seltzer categories." said second-generation winemaker Kim Kramer.

Tasting Notes: A Symphony of Flavors

Our Piquette delights the palate with a harmonious blend of flavors. Experience the compelling notes of pomegranate, cran-raspberry, rhubarb, and tart apple, complemented by subtle hints of earth and spice. Each sip of Piquette is a refreshing and vibrant journey, offering a unique taste experience unlike traditional wines.

Enjoying Piquette: Versatile and Refreshing

Piquette is a versatile beverage that can be enjoyed in various ways. Serve it chilled for a refreshing pick-me-up, or mix it into your favorite spritzer or sangria recipes for a flavor twist. It pairs wonderfully with light, summery foods like seafood, salads, grilled vegetables, or light appetizers. With its lower alcohol content, Piquette is perfect for daytime events or as a lighter alternative to wine.

Join the Piquette Revival: Embrace Sustainability and Refreshment

Be part of the Piquette revival and experience the joy of this unique and sustainable beverage. Whether planning a picnic, a leisurely day outdoors, or a social gathering, Piquette is the perfect companion. Celebrate the essence of vineyard life with this refreshing and easy-to-drink option that captures the spirit of innovation and sustainability.

Experience Piquette at Kramer Vineyards

Kramer Vineyards invites you to explore the delights of Piquette. Join us in embracing this ancient winemaking practice, reimagined for modern tastes. Visit our vineyard and savor the vibrant flavors of Piquette. This refreshing beverage embodies our commitment to sustainability and craftsmanship.

Explore our sparkling collection, including Piquette --->>>

Note: To learn more about the emerging trend of lower-alcohol Piquette in Oregon, we recommend reading "Is lower-alcohol Piquette Oregon's next big wine craze?".

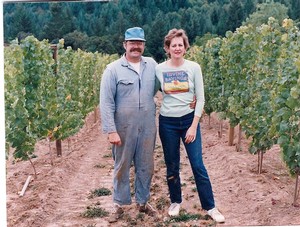

Kramer Vineyards: Crafting Unique and Refreshing Beverages Since 1990

Kramer Vineyards is a family-owned and operated winery in its second generation. For nearly 40 years, they have been growing grapes at their sustainably farmed vineyard in the Yamhill-Carlton AVA. Kramer specializes in producing cool climate white, red, and sparkling wines at their property in Gaston, 30 miles west of Portland.

Interview With Trudy Kramer

KV: How did you get in to wine?

KV: How did you get in to wine?

KV: If you could drink any wine in the world, what would it be?

Why We’re Mad for Müller-Thurgau

History

Müller-Thurgau is a white grape variety created by Dr. Hermann Müller from the Swiss Canton of Thurgau in the 1880s. The goal was to cross Riesling, capturing its rich, complex flavors with the earlier ripening Sylvaner. However, neither of these goals was achieved, nor was Sylvaner crossed with Riesling. DNA fingerprinting has revealed that Müller-Thurgau is a cross of Riesling and a grape called Madeleine Royale. As it turns out, the latter is a cross of Pinot and Trolliger. Most widely planted in Germany, Müller-Thurgau is also found in Austria, Northern Italy, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Japan, and of course, the United States.

Müller-Thurgau is a white grape variety created by Dr. Hermann Müller from the Swiss Canton of Thurgau in the 1880s. The goal was to cross Riesling, capturing its rich, complex flavors with the earlier ripening Sylvaner. However, neither of these goals was achieved, nor was Sylvaner crossed with Riesling. DNA fingerprinting has revealed that Müller-Thurgau is a cross of Riesling and a grape called Madeleine Royale. As it turns out, the latter is a cross of Pinot and Trolliger. Most widely planted in Germany, Müller-Thurgau is also found in Austria, Northern Italy, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Japan, and of course, the United States.

How we discovered MT

In 1980, vineyard owner Keith Kramer took a viticulture class at Erath every other Saturday for three months. The instructor Al Holstein, had some Müller-Thurgau planted in his vineyard. This was very exciting to another student in the class, who peppered Holstein with questions about the grape. Keith was not very interested in Müller-Thurgau initially. Still, the guy “made such a stink about it” that when the Kramers had an opportunity to buy fruit from Courting Hill Vineyard a few years later, they decided to try it. That first wine was a very fruity, off-dry white with enough potential that they went ahead and procured some starts from Sokol Blosser in the mid-1980s.

In 1980, vineyard owner Keith Kramer took a viticulture class at Erath every other Saturday for three months. The instructor Al Holstein, had some Müller-Thurgau planted in his vineyard. This was very exciting to another student in the class, who peppered Holstein with questions about the grape. Keith was not very interested in Müller-Thurgau initially. Still, the guy “made such a stink about it” that when the Kramers had an opportunity to buy fruit from Courting Hill Vineyard a few years later, they decided to try it. That first wine was a very fruity, off-dry white with enough potential that they went ahead and procured some starts from Sokol Blosser in the mid-1980s.

Müller-Thurgau emerges as our flagship white.

Müller-Thurgau was among the first wines in our tasting room for our grand opening in 1990, and it quickly gained a following. We increased the acreage in our estate vineyard to three, which does not sound like much, but this variety routinely produces 4-6 tons to the acre, double or triple the yield compared to Pinot Noir. As our production grew, we experimented with assorted styles, including sparkling wine, a dessert wine, a dry barrel-fermented wine, and a late-harvest wine. The stainless, fruity Estate bottling is our most popular wine, followed by the Celebrate sparkling wine.

It is easy to see why Muller-Thurgau is a tasting room favorite. In a region full of Pinot Gris and, to a lesser extent, Chardonnay and Riesling, Müller-Thurgau stands out. Its unique flavor profile with starfruit, lychee, melon, hints of orange blossom and gardenia, and gentle acidity with a sweet and sour effect on the palate makes it easy to sip. Plus, Müller ripens at lower sugar levels, so the alcohols in the finished wines are lower than many table wines, usually around 11%.

It is easy to see why Muller-Thurgau is a tasting room favorite. In a region full of Pinot Gris and, to a lesser extent, Chardonnay and Riesling, Müller-Thurgau stands out. Its unique flavor profile with starfruit, lychee, melon, hints of orange blossom and gardenia, and gentle acidity with a sweet and sour effect on the palate makes it easy to sip. Plus, Müller ripens at lower sugar levels, so the alcohols in the finished wines are lower than many table wines, usually around 11%.

Game of Clones: Pinot Noir

I never really gave a clonal choice too much thought until recently. As a second-generation winemaker with an established vineyard, our clonal selections were made many years before I decided to pursue a career in wine. Why focus on this aspect when so many variables are at play—soil type, elevation, vine density, vine age, slope, trellis system, own-rooted or grafted? Aside from the differences in ripening time, are the clones of Pinot Noir all that distinguishable, or is it trivia?

There are more available clones of Pinot Noir than any other grape variety. When we established our vineyard in 1984, three clones were available: Pommard, Wädenswil, and Gamay Beaujolais. The Dijon clones, such as 114, 115, 667, etc., began entering Oregon in the late 80s and early 90s. These clones may differ in several ways—cluster size and shape, berry size, color, early or late ripening, etc. Now there are over 50 clones of Pinot Noir available in the United States, and we’re up to 9 at our estate.

As interest in these new clones has increased, we began to study them more closely in our vineyard. The higher crop levels in 2014 led us to introduce a series of single clone wines of Pinot Noir: Dijon 115, Dijon 777, and Pommard. We followed similar winemaking protocols for these to allow for the most explicit clonal expression possible. The fruit was harvested by hand, and 25% whole clusters were layered on the bottom of 1-ton vats and topped with destemmed fruit. After a 5-day cold soak, fermentation began. The must was pumped over, punched down twice daily, and pressed at dryness. The wine was aged in neutral French oak barrels for 14 months and bottled.

This limited collection is available in our online store.

A Big One for Sparkling Wines

Kramer Vineyards harvest larger than ever before

Kramer Vineyards celebrates its largest harvest in 30 years with a record-breaking offering of sparkling wine. Winemaker Kim Kramer's passion for sparkling wines, known for their precision, brings delight to wine lovers. To further celebrate, the family-owned winery will offer 14 sparkling wine releases.

“We’ve always loved sparkling wines. They are extremely challenging to make because they’re wines of such precision,” said Winemaker Kim Kramer, who’s been producing sparkling wines since the early 2000s. “It’s rewarding to see the delight these wines bring to people’s faces and to see them return for more.”

“We’ve always loved sparkling wines. They are extremely challenging to make because they’re wines of such precision,” said Winemaker Kim Kramer, who’s been producing sparkling wines since the early 2000s. “It’s rewarding to see the delight these wines bring to people’s faces and to see them return for more.”

Dedicated to sharing the delight of its fizzy wines while quenching the thirst of a growing sparkling wine demographic, Kramer started its own sparkling wine club.

Kramer Vineyards is releasing a new collection of traditional method sparkling wines from its estate vineyard in the Yamhill-Carlton AVA to celebrate the bounty of the harvest. These wines are all bottle fermented and composed of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and/or Pinot Meunier. This traditional sparkling collection includes vintage and nonvintage Brut, NV Brut Reserve, NV Brut Blanc de Blancs, NV Brut Blanc de Noirs, and NV Brut Rose. Kramer has been experimenting with extended tirage sparkling wines, so expect to see those releases.

If you want more information about this topic, please get in touch with Kim Kramer at (503) 662-4545 or email at kim@kramervineyards.com.